Articles

Federal contractors share pain of longest-ever government shutdown

Washington,

May 11, 2019

Tags:

Federal Employees

Fairfax County Times |

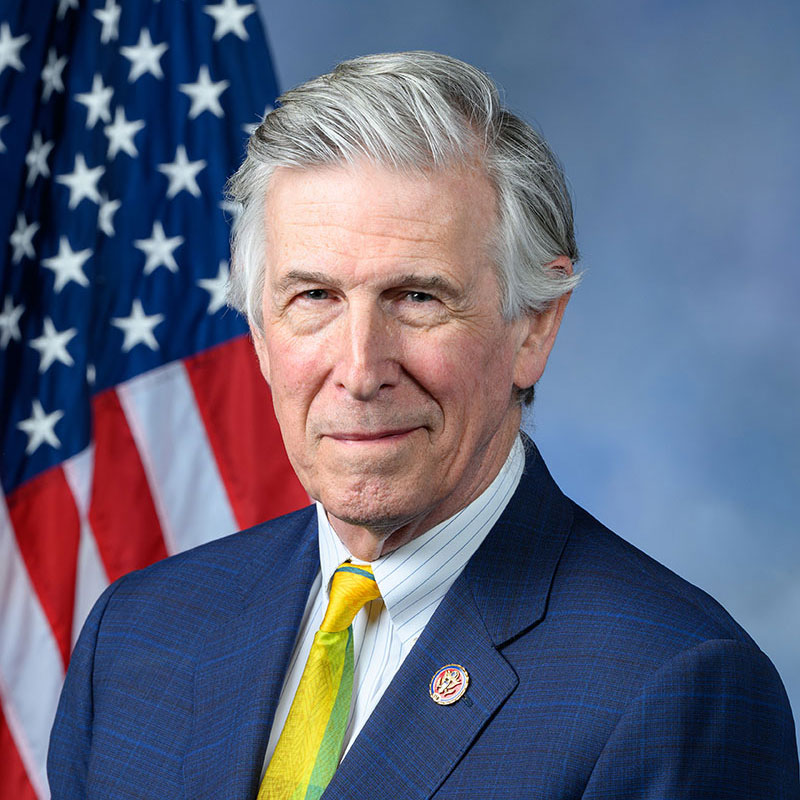

The 35-day shutdown that brought much of the federal government to a standstill in January has mostly left front pages and cable news cycles, supplanted by more recent crises, but for many workers and businesses in Northern Virginia, the pain of that experience still lingers almost four months later. A special police officer for 17 years, Tamela Worthen started her new job as a security officer at the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C., on Nov. 14, 2018. 39 days later, Worthen was put on furlough when key federal agencies, including the Department of Homeland Security and Justice Department, closed because Congress and the White House failed to adopt appropriations bills by a Dec. 21 deadline. As the shutdown dragged on, eventually turning into the longest in U.S. history, Worthen and her fellow contract workers had to make ends meet while knowing they might never see a paycheck. After a lifetime of working to ensure she consistently paid her bills on time, Worthen struggled to stay afloat. A suddenly faltering credit score made possible steps like finding another job or refinancing her house difficult. An inability to pay her health insurance premium or buy medications she needs to treat diabetes and a heart disease resulted in a hospital trip, which led to two more bills on top of a mortgage, electricity bills, car insurance, debt payments, and unemployment benefits that need to be repaid. “I still can’t pay [the hospital bills], but I had to get emergency assistance to see what was going on with me,” Worthen said. “That’s what I don’t like…You go back to work. You get your money, but you still got bills piled [up]. When is it going to stop?” Worthen is one of several contract workers and business owners who detailed their experiences with the federal government shutdown at a Congressional field hearing on May 6. As chairman of the House Subcommittee on Government Operations, Rep. Gerry Connolly (D-Va.) presided over the hearing, which was held at George Mason University in Fairfax. Fellow Reps. Jennifer Wexton (D-Va.), Don Beyer (D-Va.), Jamie Raskin (D-Md.), and Eleanor Norton (D-D.C.) were also in attendance. Delivered by witnesses ranging from employees like Worthen to corporate leaders like Leidos CEO Roger Krone, the two-and-a-half hours of testimony made clear that, while the shutdown officially ended on Jan. 25, contractors and other businesses that depend on the government are still grappling with the closure’s impact. “We need to do better for our employees,” Wexton said. “We need to do better for our contract workers, especially as there’s more pressure on the government to do more work with contract employees.” Approximately 800,000 contractors from 10,000 companies across the U.S., along with 400,000 federal employees, were directly affected by the federal government shutdown. While Congress approved legislation in January guaranteeing back pay to federal employees once the shutdown ended, bills doing the same for contractors have languished in committees. With no paycheck coming in and expenses adding up, some contract employees left to find new jobs during the shutdown. About 600 members of Service Employees International Union 32BJ, which represents 20,000 sub-contracted federal workers in the D.C. region, were affected by the government’s closure, many of them already earning $35,000 or less and working multiple jobs. 35 security guards at the Smithsonian Institution, some of them veterans, quit because they were unable to stay and feed their families, 32BJ SEIU Vice President Jaime Contreras says. “They felt betrayed by their country,” Contreras said. According to Connolly’s office, federal contracts contribute $66 million to the D.C. metropolitan region’s economy every week, and Virginia’s 11th Congressional district alone boasts at least 70,000 contractors, who represent over 16 percent of the employed workforce. In a report released on Jan. 28, the Congressional Budget Office estimated the partial shutdown delayed $18 billion in federal spending. That reduced economic activity dropped the real gross domestic product in the fourth quarter of 2018 by $3 billion and in the first quarter of 2019 by $8 billion compared to what would have been produced otherwise. About $3 billion of that GDP will never be recovered, amounting to 0.02 percent of the projected annual GDP in 2019, according to the budget office report. Small and midsized businesses bore a disproportionate amount of the shutdown’s impact, lacking the resources to weather a sudden loss of revenue and labor. U.S. Chamber of Commerce data from Jan. 24 showed that the shutdown negatively affected 41,000 small businesses across all 50 states, costing small government contractors $2.3 billion in revenue, according to Nextgov. Leidos, a 32,000-worker information technology and science company based in Reston, lost $14 million in revenue and halted 22 programs, affecting 200 subcontractors, about half of which were small businesses, according to Krone’s testimony. The shutdown left 893 Leidos employees with nothing to do since the federal agencies they work with closed, but the company’s size gave it the ability to reallocate those workers to open positions, mostly on contracts with the Department of Defense, which was still funded. Chantilly-based government services firm Citizant, Inc., paid the 30 affected employees in its 180-person workforce throughout the shutdown after collecting nearly 2,500 hours through a leave donation program. In the process, however, the business lost $430,000 in revenue and went more than $4 million in debt, since employees continued working on projects as required by contract, even though the federal employees who process invoices were furloughed. With a $700,000 payroll and at the limit of its borrowing capacity, Citizant postponed paying its vendors until early April and was within days of having to decide whether to declare bankruptcy, according to founder and CEO Alba Alemán. “It’s going to take years to recover from that,” Alemán said when asked about the shutdown’s effect on recruiting. “You’re not going to be able to draw that top talent into our marketplace, so it’s a real concern.” Even some private businesses that are not federal contractors felt an impact from the shutdown. Wesley Ford serves as president of the D.C. café TKI Coffee, which is located in a federal agency building and counts federal employees and people visiting government offices as 90 percent of its customers. TKI remained open, but Ford says a drop in revenue combined with rent forced him to lay off 40 percent of his staff so that they could apply for unemployment benefits, and the remaining staff saw their hours reduced. Norton and Reps. Donald Norcross (D-N.J.) and Ayanna Pressley (D-Mass.) have introduced bills to give back pay to federal contract workers. Sen. Tina Smith (D-Minn.) is sponsoring Pressley’s Fair Compensation for Low-Wage Contractor Employees Act of 2019 in the Senate. Connolly hopes Congress can also find a way to allow contract provisions that would provide a safety net to federal contractors in case of another shutdown. That would be especially critical in Northern Virginia, where contractors outnumber federal employees by 50 percent, according to the Congressman. “They often are embedded in the federal agency working side-by-side with a federal employee, except the federal employee gets reimbursed, the federal contract employee not necessarily,” Connolly said. “…Hopefully, we don’t ever shut down the government again, but if we do, we want to try to see if we can protect these employees as well.” |