Articles

Washington Post: Congress to consider bill requiring police to report their misconduct settlementsCities and counties pay millions to victims of police abuse; collecting data may promote reform, sponsors say

Washington,

March 5, 2021

Tags:

Equality

Originally published by the Washington Post

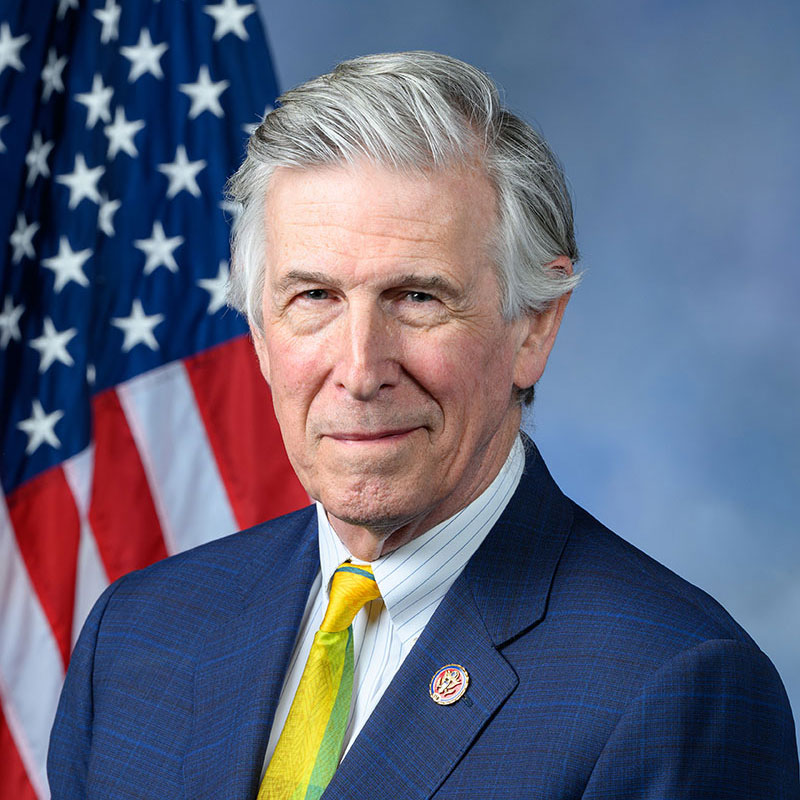

Congress to consider bill requiring police to report their misconduct settlementsCities and counties pay millions to victims of police abuse; collecting data may promote reform, sponsors sayByTom Jackman March 5, 2021 at 7:23 p.m. EST Last year, officials in Prince George’s County paid $20 million to the family of a handcuffed man who was killed by a police officer. In Washington, city officials paid out $40 million to victims of police abuse between 2016 and 2020. Chicago paid more than $709 million to police victims in a recent eight-year period. Taxpayers absorb the costs of those payouts annually. But the settlements and judgments are reported sporadically, hiding the effect on city and county services that are often raided to pay the costs of police misconduct, and the long-term debt it creates. So two members of Congress from Virginia, Sen. Tim Kaine (D) and Rep. Don Beyer (D), have introduced a bill that would require law enforcement agencies to report all police-related judgments and settlements, including financial costs and court fees, to a central database maintained by the Justice Department. Some policing experts have long thought that exposing the financial cost could reduce such misconduct, by causing municipalities and their insurers to crack down on actions that hurt them financially. And “you can’t manage what you don’t measure,” Beyer said in an interview. “So let’s measure it and make it transparent and see how the taxpayer reacts to it.” Not all settlements are related to conduct by officers on the street. Many large payouts are related to false convictions and wrongful imprisonments caused by corrupt police investigations. Chicago had to launch a separate “reparations fund” for victims of one detective who forcibly coerced confessions for decades from people who hadn’t committed crimes. “This bill is tackling extremely important issues,” said Joanna C. Schwartz, a UCLA law professor who has written extensively about police misconduct litigation. “Civil rights lawsuits are too often treated by local governments simply as the cost of doing business. Cases are defended by city attorneys’ offices, money from central funds are spent to resolve the cases, and no effort is taken to gather and analyze information from those lawsuits in ways that might reduce the likelihood of future harms.” Beyer and Kaine’s Cost of Police Misconduct Act would require all law enforcement agencies that receive federal funds to report every judgment or settlement along with the type of misconduct, the internal personnel action taken against the officer, the source of money used to pay a judgment or settlement, and the total amount spent on such payments including bond interest and other fees. “This is our best effort to get all that data out there,” Beyer said. “And hopefully state and local governments will say, ‘Instead of paying off misconduct victims, why don’t we invest in better training and more mental health training?’ ” “Police misconduct causes real harm to real people,” Kaine said in a news release, “and the erosion of trust in our justice system and the many good people who work in it.” He said the bill would “require transparency, giving the public powerful information that will spur reform.” Schwartz said that when she investigated the issue with police and local governments across the country, “I found that many large cities did not know the most basic information about the amount of taxpayer dollars spent each year to resolve police misconduct settlements and judgments.” Collecting such information “will not on its own transform policing,” Schwartz said. “But it will create a path for more introspection among departments about their officers’ behavior.” The deeply researched 2018 study by the Action Center on Race and the Economy, titled “Police Brutality Bonds: How Wall Street Profits from Police Violence,” dug into the details of how municipalities fund their misconduct payouts. The authors found that some cities and counties habitually use bonds as part of their budgets, but police departments regularly exceed their allotted settlement budgets, knowing they will get the additional money from local elected leaders when they ask for it. They found that some cities — including Bethlehem, Pa.; South Tucson; and Cleveland — have had to raise taxes to cover the costs of police settlements, that individual officers and their departments are shielded from financial consequences, and that settlements “can function as a kind of predatory silencing of victims and families” by requiring them to sign confidentiality agreements in order to receive payment, serving to “prevent accountability for violent officers and their departments.” Sometimes municipalities pay big settlements even before a lawsuit is filed or a criminal case is resolved. Baltimore paid $6.4 million to the family of Freddie Gray, who died in police custody in 2015, before any trials of the officers involved. Prince George’s County in September paid $20 million to the family of William Green, fatally shot as he sat in the front seat of Cpl. Michael A. Owen’s cruiser eight months earlier. Owen, who is awaiting trial on a murder charge, told authorities that he had feared for his life because Green reached for his firearm. Prosecutors say there is no evidence that Green posed a serious threat. And a Washington Post investigation last year found that D.C. had spent $33 million since 2016 on six claims of wrongful conviction or death, an additional $2.8 million to settle remaining lawsuits over police conduct during World Bank protests in 2002, and $5 million to resolve 65 other suits alleging false arrest, excessive force and other violations. “Most citizens have no idea what police misconduct actually costs their cities,” said Chuck Wexler, executive director of the Police Executive Research Forum, which advises many big city police departments, “and when they hear the judgments they are astounded.” But, Wexler added, the judgments "only make the arguments to defund the police more ludicrous. Preventing police misconduct requires significant investment in hiring, policy and training the next generation of forward-thinking cops.” John Rappaport, a University of Chicago law professor who studies policing, has written that “liability insurance may be a viable route to police reform.” In an opinion piece in The Washington Post, he wrote that “insurers work closely with the police to promulgate and update departmental policies on critical policing tasks” and that “some insurers put pressure on agencies to ‘correct’ or even terminate so-called problem officers.” Rappaport said states can use insurance regulation “to shape the terms (and prevalence) of police liability insurance policies, which, in turn, should influence police behavior.” With police reform still a focus of Congress with the House’s recent passage of the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act, Beyer said that Kaine will try to offer their bill as an amendment to the Floyd Act in the Senate, and hope for its passage there and in conference with the House. |