Articles

Ex-Lobbyist for Foreign Governments Helped Plan Pruitt Trip to Australia

Washington,

May 2, 2018

New York Times

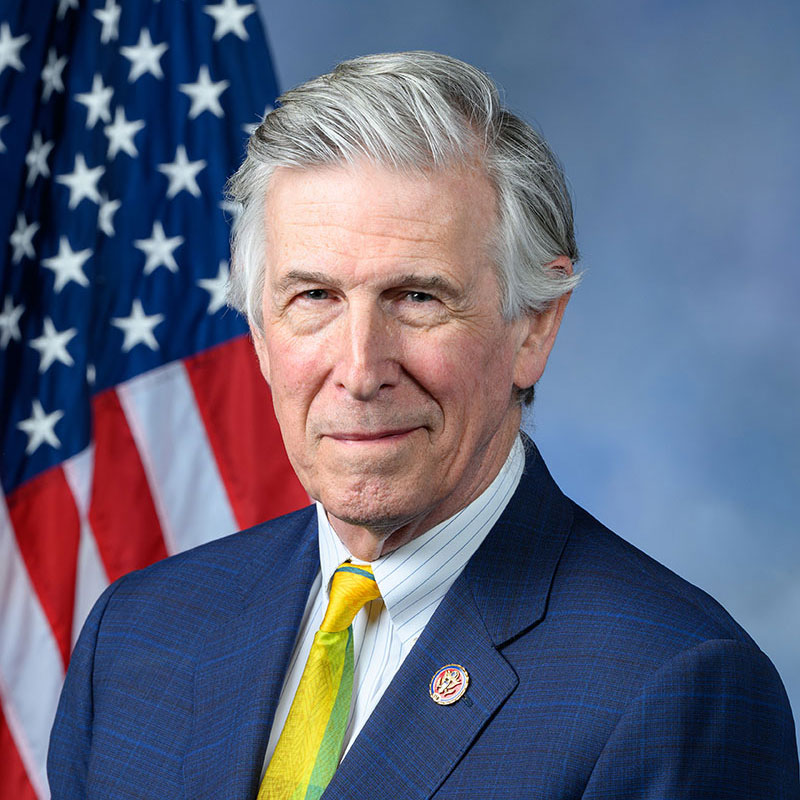

A Washington consultant who was removed from President Trump’s transition team for using his business email address for government work played a central role last year in planning a trip to Australia for Scott Pruitt, the head of the Environmental Protection Agency, and then took steps to disguise his role, new documents show. The consultant, Matthew C. Freedman, who is also a former lobbyist for foreign governments, runs his own corporate advisory firm and is treasurer of the American Australian Council, a group that helps promote business for American-based companies in Australia. Two prominent members include Chevron and ConocoPhillips. Though the Australia trip never happened — it was canceled after Hurricane Harvey devastated much of the Texas Gulf Coast — it shows a pattern in which Mr. Pruitt has repeatedly relied on people with clear business interests to shape the agenda of his foreign travel. Separately last year, a trip to Morocco was organized by a lobbyist who later was hired by Morocco as a $40,000-a-month foreign agent to represent its interests abroad. Mr. Freedman has spent decades as an international political consultant and lobbyist, starting in the 1980s as an employee of Paul Manafort when the two men worked together to help the embattled Philippine dictator Ferdinand Marcos. Mr. Manafort later became Mr. Trump’s campaign chairman, and many of his former lobbying associates entered Mr. Trump’s orbit, with some remaining in influential positions well after Mr. Manafort resigned from the campaign amid scrutiny of his work for Russia-aligned Ukrainian politicians. Mr. Manafort has since been indicted on charges related to that work by the special counsel investigating Russian interference in the 2016 election. Mr. Freedman worked on Mr. Trump’s transition team in late 2016 on national security-related issues. He was removed after conducting government business using an email address associated with his consulting firm, Global Impact Inc., which fed the impression that he was using his position with the transition team to drum up business, according to an adviser to the transition. More recently, Mr. Freedman advised Mr. Trump’s new national security adviser, John R. Bolton, as he prepared to take office, according to two people familiar with the arrangement. They said that he had worked as a special government employee during the Trump administration — a position that allowed him to maintain his outside consulting business while working for the federal government. Mr. Freedman declined to comment. A statement he provided to The New York Times from the American Australian Council said that the group had authorized him to have discussions with the E.P.A. about the possible trip to Australia, “to further the mission” of the organization. Mr. Pruitt still has the support of Mr. Trump, a top White House official said Tuesday, despite the fact that Mr. Pruitt faces 11 investigations into his spending and management practices at the E.P.A. Jahan Wilcox, a spokesman for Mr. Pruitt, said that the agency’s staff was in charge of planning the Australia trip and that Mr. Freedman’s involvement began in mid-2017. However, emails released recently under the Freedom of Information Actto the Sierra Club, which sued to obtain the documents, appear to contradict that. The emails indicate Mr. Freedman was involved in early March, just weeks after Mr. Pruitt was confirmed as the E.P.A. chief, in coming up with reasons to justify a trip by Mr. Pruitt to Australia. Representative Don Beyer, Democrat of Virginia, who has been critical of Mr. Pruitt’s spending, said the emails help to document allegations raised by Mr. Pruitt’s former deputy chief of staff, Kevin Chmielewski, who had questioned Mr. Pruitt’s travel spending before being pushed out of the agency earlier this year. “Pruitt’s trips began with Pruitt ordering staff to ‘find me something to do’ to justify his expensive travel,” Mr. Beyer said, quoting Mr. Chmielewski. Mr. Beyer said that the emails “also reveal that lobbyists for energy companies and foreign governments acted as travel agents.” The Australian embassy said in a statement that it was unaware that Mr. Freedman had been working to arrange the trip, and that neither Mr. Freedman nor his company “has been engaged to represent Australia.” The embassy added that the American Australian Council, for which Mr. Freedman serves as treasurer, “is an independent organization that does not represent the Australian government.” Mr. Freedman advises global corporations seeking to break into the Australian business market, according to someone familiar with his work. Mr. Freedman frequently discussed the possible Australia trip with another lobbyist, Richard Smotkin, who has longstanding ties to Mr. Pruitt. Mr. Smotkin also helped organize Mr. Pruitt’s December trip to Morocco, and then four months later signed the $40,000-a-month contract to represent an arm of the government of that North African country. Michael Brune, executive director of the Sierra Club, said in a statement, “It’s no wonder these emails had to be forced out by a court: They expose the fact that corporate lobbyists are orchestrating Pruitt’s taxpayer-funded trips to push their dangerous agendas.” The emails with Mr. Freedman were among a collection of 6,337 pages of correspondence between corporate representatives and top political appointees at the E.P.A. Most were sent to Millan Hupp, a top political aide to Mr. Pruitt. Ms. Hupp also worked with Mr. Pruitt as a political assistant when he was Oklahoma’s attorney general. Ms. Hupp served as a gatekeeper for Mr. Pruitt with companies and organizations interested in getting on his calendar or inviting him to an event, the emails indicate. Those companies have included the coal producer Peabody Energy and Koch Industries, the conglomerate controlled by the billionaire brothers David and Charles Koch, as well as dozens of others, with a particular emphasis on fossil-fuel-related firms and chemical industry and agriculture groups such as the American Farm Bureau. Mr. Freedman is not registered as a lobbyist for the government of Australia, nor is he currently registered to lobby on behalf of any foreign or domestic clients in the United States, according to records on file with Congress and the Department of Justice. They show that a now-inactive firm he had formed with Mr. Manafort was last registered to lobby in the late 1990s, when it represented the government of Nigeria and the Argentine politician Alberto Pierri. Mr. Freedman’s associates say he continues to advise international clients in various capacities that do not trigger lobbying disclosure requirements. In the emails, Mr. Freedman offered Ms. Hupp a series of suggestions as to whom Mr. Pruitt could meet with on the trip to Australia. Mr. Freedman said he had already been talking to top government officials there to get the planning started. “I’ve been in direct contact with the Minister in Aus, and we will be speaking with his senior staffer (Cosi) who is the lead from their side on Monday night,” Mr. Freedman wrote to Ms. Hupp in late June, as the planning for the trip got underway. “Also, Jim Carouso, the Charge at the US Emb in Canberra is a close personal friend and would likely have good inputs, but I want to wait a bit before I contact him.” In a separate email, he suggested Mr. Pruitt meet with top Australian officials including Foreign Minister Julie Bishop and Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull. And he went on to suggest topics that could be discussed at the meeting, including “the current US Australian environmental agreements that are currently in place and whether they should be changed or updated or canceled or replaced.” Mr. Freedman placed a condition on the assistance he was providing: His involvement should not be disclosed. “Rick and I will be present but not listed as members of the delegation,” Mr. Freedman wrote, referring to Mr. Smotkin. Ms. Hupp’s input in these email exchanges was short, with notes back to Mr. Freedman like “Sounds good. We will plan for Monday morning,” in response to a request in July from Mr. Freedman to discuss the Australia trip. The exchanges showed an awareness that traveling to Australia would have its complexities, given that Mr. Pruitt is a climate change skeptic. “There are challenges to a visit,” Mr. Freedman wrote in one March 2017 memo, as the debate over the trip first started. “It would highlight the Australian Government aggressive support for policies that may not be in sync with the Trump Administration, and the strong financial role played by the Australian Government in protecting the environment.” Later, on July 18, Mr. Freedman wrote to Ms. Hupp to say that Mr. Pruitt should be prepared for a “confused and angry group of Aussies” who were likely to disagree with Mr. Trump’s policies. On climate change specifically, Mr. Freedman wrote that he had been in touch with the executive director of the Institute of Public Affairs, an Australian think tank that he described as being “aligned with the Trump vision on various issues” including coal and deregulation. Mr. Freedman said he planned to suggest more people Mr. Pruitt should meet through that organization. The emails released to the Sierra Club also provide further documentation of the role that Mr. Smotkin played in setting up Mr. Pruitt’s December visit to Morocco. Ms. Hupp turned to Mr. Smotkin in September to set up a meeting with the Moroccan ambassador to the United States. “Would you be so kind as to pass along these three dates as potential for a meeting with the Moroccan Minister?” Ms. Hupp wrote to Mr. Smotkin. He agreed to do so, and wrote back to correct the title: “Will do. It is the ambassador.” Though the trip to Australia was ultimately canceled, vouchers previously released by the E.P.A. show that two aides and three security officials spent about $45,000 traveling there to set up meetings and prepare for Mr. Pruitt’s arrival.

|