Think Progress

Staff departures from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) have become so common that they rarely make news anymore — since Administrator Scott Pruitt took control of the EPA in 2017, more than 700 employees have left the agency.

But this week, as federal investigations surrounding Pruitt’s ethical scandals continue to mount, four departures in particular made headlines, as officials with close ties to the administrator announced they would be moving on from the agency.

The high-profile departures come at a time when Pruitt appears to be fighting for his job in both public and private arenas. The departures are especially notable because three of the top officials appear — at least in some way — connected to one of the ethical scandals that have dogged Pruitt over the last month.

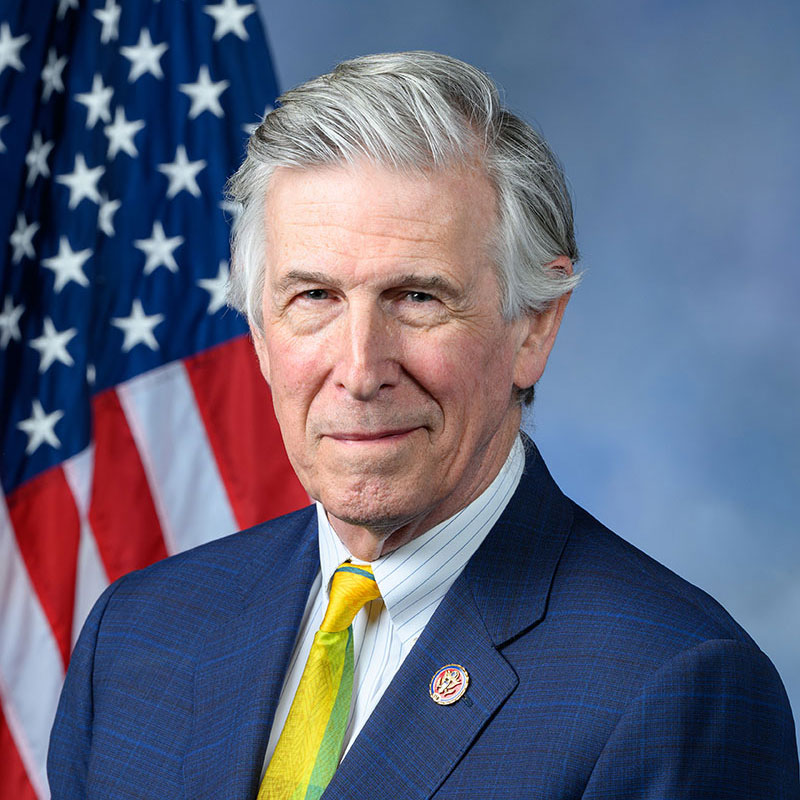

“Administrator Pruitt has repeatedly and unapologetically blamed his own staff for the crisis of leadership that he has created at EPA,” Rep. Paul Tonko (D-NY), the ranking Democratic lawmaker on the House Energy and Commerce’s Subcommittee on the Environment and a vocal critic of Pruitt’s, said in a statement emailed to ThinkProgress. “I don’t know why senior officials are abandoning him now in such great numbers, but many of these departing staff have overseen or directly contributed to mismanagement that has undermined public trust and the agency’s ability to fulfill its mission to protect public health.”

On Tuesday, both Pruitt’s head of security Pasquale “Nino” Perrotta, and the head of the EPA’s Superfund program Albert “Kell” Kelly announced that they would be leaving the agency.

Perrotta’s resignation came just a day before he was scheduled to testify before the House Oversight Committee regarding Pruitt’s spending on first-class travel and other expenses that the EPA has defended as necessary for security. According to Politico, Perrotta was a “driving force” behind much of Pruitt’s lavish spending on security measures, “goading” him into spending more for security and travel.

Kelly, who came to the EPA after being banned for life from the banking industry by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, had also been facing scrutiny from Democratic lawmakers over his appointment to streamline the EPA’s Superfund program, which handles cleanup of polluted sites across the country. Kelly also declined to testify before Congress regarding the EPA’s Superfund cleanup program.

But Kelly has long been a loyal supporter of Pruitt’s. In 2003, Kelly helped Pruitt finance a mortgage on a house that Pruitt bought from a retiring telecommunications lobbyist. Kelly reportedly also cancelled a trip to West Virginia — where he was scheduled to visit a town contaminated by toxic chemicals — to stay in D.C. and help Pruitt handle fallout from numerous controversies.

During oversight hearings before two Congressional committees last week, Pruitt was repeatedly asked questions about Kelly’s appointment to the EPA and whether Kelly would agree to testify before Congress.

Two days after Kelly and Perrotta announced their resignations, Liz Bowman, the top communications official at the EPA, announced that she would also be leaving the agency to take a job as communications director for Sen. Joni Ernst (R-IA).

Bowman was one of the agency employees who received a sizable raise last year via a provision in the Safe Drinking Water Act, which allows the EPA administrator to hire up to 30 employees without Congressional approval.

Pruitt has come under scrutiny for using the loophole to give raises to political appointees without approval from the White House. Initially, Pruitt said he did not know about the raises, but later admitted that he had given his chief of staff authority to authorize the pay increases. The raises are part of an ongoing investigation by the House Oversight Committee.

On Friday, an administration official told the Washington Examiner that John Konkus, the agency’s second highest-ranking communications official, would also be leaving the agency. Konkus was a political aide who had received approval to work as a media consultant for outside groups including a Republican firm.

Publicly, the EPA has been adamant that these departures do not reflect any kind of internal issues within the agency. Bowman, like Kelly and Perrotta, told reporters that her departure has nothing to do with the ongoing investigations and scandals surrounding her boss. But at least one Democratic representative — Rep. Don Beyer (D-VA) — points to the stream of resignations as proof of Pruitt’s failures as an EPA administrator.

“Scott Pruitt’s toxicity has infected the upper echelons of EPA leadership, and the process of cleaning this mess must begin with Pruitt’s dismissal,” Beyer said in a statement on Friday.

But what if instead of signaling a weakening of Pruitt’s leadership, the resignations are in fact a gambit to secure his position?

During his Congressional oversight hearings, Pruitt made a point of placing blame for a number of scandals squarely on the shoulders of EPA employees, rather than taking the blame himself.

By shedding himself of people associated with these scandals — particularly Perrotta, who has been implicated in the issues with taxpayer funds being spent on security, and Bowman, who is part of the raise scandal — Pruitt is effectively creating a firewall between himself and controversy that, at certain points, has seemed to threaten both his future as EPA administrator and his well-documented political aspirations.

The string of high-profile departures might be bad optics for Pruitt, at least in the short term, but they will allow the administrator to further remove himself from culpability with respect to various ethical scandals. It’s certainly a gamble — especially when Pruitt is trying to impress a boss who appears concerned with appearances above all else — but one that could ultimately help Pruitt cement his position at the helm of the EPA for years to come.